Is Blood On The Tracks autobiographical?

Recalling the ups and downs of writing my first book twenty years later.

Opinions are, well, everybody’s got one. Heard that one? Of course you have. Here I will offer you my opinion of a book of opinions I co-authored in 2003-2004, secluded in a blue music studio. Blue as the paint on the walls, my life imitated art. The break-up album I was researching morphed into my own divorce.

Following the book rollout/BOTT band reunion concert at The Pantages Theater in Minneapolis, I found myself in mens group sessions quoting “Idiot Wind” on the heels of my own divorce. “Now everything’s a little upside down, as a matter of fact the wheels have stopped, what’s good is bad, what’s bad is good, You’ll find out when you reach the top, you’re on the bottom”.

That summer I heard Steve Berkowitz’ Super Audio Compact Disc remixes, a short-lived 4-track format, now extinct. Hearing my guitar part prominently on the right rear speaker on Tangled Up In Blue for the first time perked up my spirits. A ray of hope appeared as I discovered that I had somehow played better in those six minutes of Tangled Up In Blue than I had ever or would ever play in my lifetime. I heard my guitar on the intro and again at the four minute mark interacting with Bob’s as the performance builds intensity.

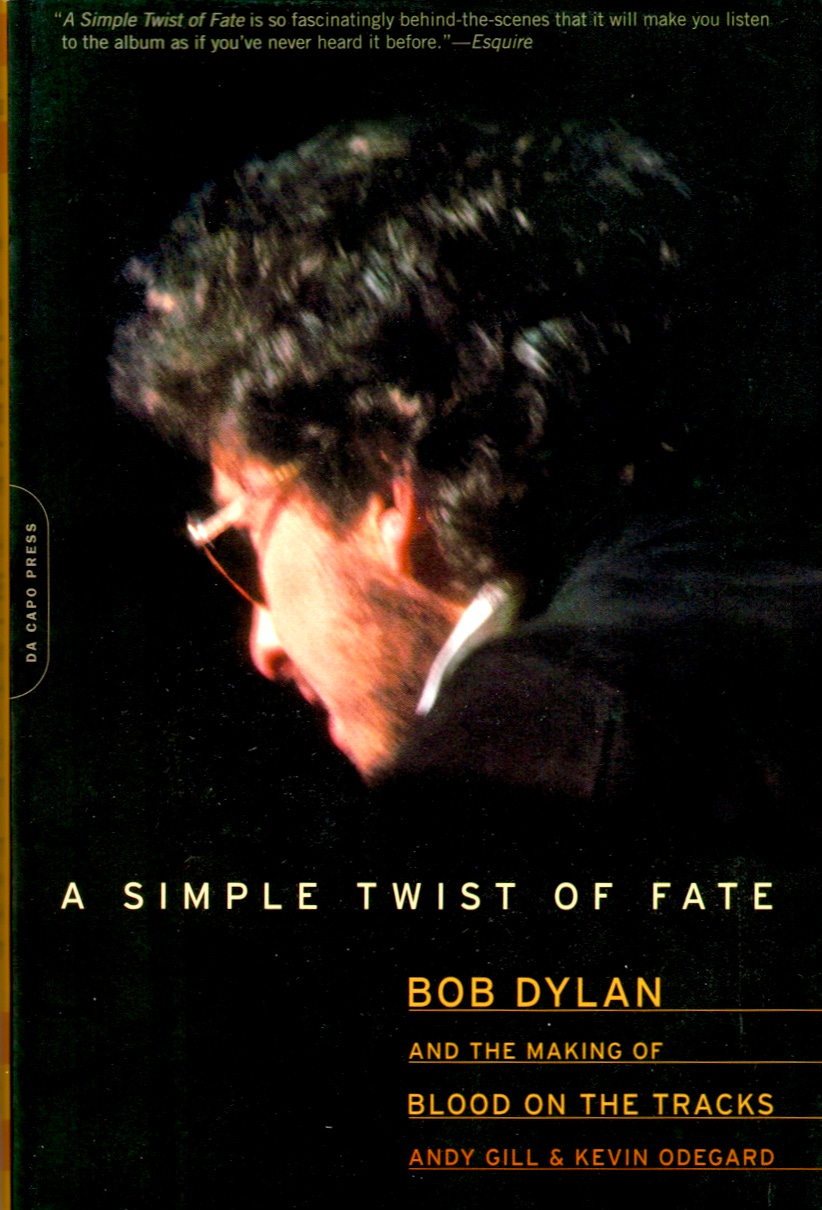

Our book, “A Simple Twist Of Fate: Bob Dylan and The Making Of Blood On The Tracks”, remains in print at this writing, available at all online booksellers.

Critics were fair, then and now. No single fact, date or attribution in our book has ever been challenged. I told the story as a firsthand witness and left my own opinions on the editing room floor.

My collaborator Andy Gill, whom I never met in person, opens the book with his description of the state of musical affairs leading up to 1974. Readers got cranky about our subjectivity and let us know. Fortunately we had a wise-beyond-his youth editor in Ben Schafer who rode continuity to establish and retain a flow. When pop music maven Jon Bream read it, the first thing he said to me was, “I can tell exactly, sentence by sentence, which sections you wrote, apart from Andy Gill’s”.

At the time, I knew I was lucky to get the deal; that it was contingent upon collaborating with an established author made me the junior partner, mediator, go-between and errand-boy for the duration, a role which I eagerly accepted.

Readers fell into two categories, as they remain today. Musicians and Bob fans seem to like the tech-y details I brought to the project; guitar makes, mics, verbatim engineering and production notes and recollections of the six Minnesota musicians. Other readers, as we find among diners when they are miffed at a bad waiter on Yelp, are less kind, picking at their trifles with a lobster fork. “It’s too short”. “There are no Dylan interviews”. “It’s all been said before”. No, it hasn’t, dear readers, and if you want to hear the whole Minnesota story be sure to get “Blood In The Tracks”, Paul Metsa and Rick Shefchik’s completist story of the Minnesota sessions and musicians.

Andy Gill interviewed NYC engineer Phil Ramone and most of the September, 1974 New York City session players. Andy lays out the sad tale of the frustrated New York cats whose work was almost entirely cut from the Columbia release on January 20, 1975. Phil Ramone’s work was cut in half. He was not pleased about it, but it was Bob’s decision and ultimately didn’t impact Ramone’s trajectory to the top of his profession.

You can hear it all now on More Blood, More Tracks, the 2018 Columbia 6-disc release containing every take of every song, with one notable exception. “Idiot Wind” with Tony Brown’s bass and Paul Griffin’s spooky overdubbed organ were left off the release. More Blood, More Tracks puts us in the studio for a fascinating look at Dylan’s work style, his perfectionist drive to get the words and music just right.

Surprisingly, it’s not boring. I can listen straight through in an afternoon and, much like viewing Francis Ford Coppola’s extended 7-hour NBC broadcast of The Godfather Epic. This is an epic entertainment, a master class in song crafting A to Z. Columbia Legacy Records has spared no expense releasing official ‘bootleg’ after ‘bootleg’. Their multi-disc bootleg of the Blonde On Blonde sessions is a personal favorite.

Other readers, as we find among diners when they are miffed at a bad waiter on Yelp, are less kind, picking at their trifles with a lobster fork. “It’s too short”. “There are no Dylan interviews”. “It’s all been said before”. No, it hasn’t, dear readers, and if you want to hear the whole Minnesota story be sure to get “Blood In The Tracks”, Paul Metsa and Rick Shefchik’s completist story of the Minnesota sessions and musicians.

Is Blood On The Tracks autobiographical?

On Mary Travers’ radio show, Dylan responded to a well-intentioned compliment on Blood On The Tracks, saying he didn’t know how people can relate to “That kind of pain”. Then Jakob Dylan was quoted saying about the album “That’s my mom and dad talking”. Chekov? I don’t think so.

I understand interviews now, fifty years on. I know how things can slip out. I allowed whole passages to slip out in print In all three editions of our book. Things I could have cut. Hurtful things that needn’t be said about people I loved, a family whose trust I betrayed. Regrets? I’ve had a few.

Did Bob write his breakup masterpiece based on his own life? Not entirely, but even the allegorical characters of Lily, Rosemary, the Jack of Hearts bear more than a passing resemblance to certain folks in and around his North Country haunts of old. I could swear Larry Kegan’s ghost inhabits one or more characters on Blood On The Tracks. If there is direct overlap from Dylan’s own experience, it’s the psychic pain he reveals in spilling his guts. Divorce can be a wrenching ordeal for the whole family, and Bob has a very large family, especially when you consider the wannabe’s, would-be’s and total imposters. The latter are legion in Minnesota, New York, California and elsewhere.

Does Blood On The Tracks still resonate with our experience? Growing in stature as the years go by, still selling at the top end of his body of work, the answer is yes. Dylan’s lyrics have always been a fluid amalgam; dada-esque, from the ether transmuted. Even Bob Dylan doesn’t claim to know how he’s wired; just that he was, is and will ever be.

First thing every morning I recite my two favorite Dylan quotes to start my day on the right note. “If I’ve ever had anything to tell anybody, it’s that: You can do the impossible; anything is possible. And that’s it; no more”, and this: “A man is a success if he gets up in the morning and goes to bed at night and in between does what he wants to do”. To Bob the songwriter, the painter, the metal sculptor and the role model who came into my life when I needed one, I say thank you.

Dylan’s recorded body of work has been studied, PHD’d, analyzed, reversed, anagrammed, posterized, pasteurized, homogenized, covered, banned, censored, redacted, spin-dried and proven time out of mind to mean different things to different people. That’s the way our most revered laureate has said that he likes it; open-ended, subject to all interpretations, reflecting a civilization that changes with the amorphous hues of day turning to night.

*The Tangled Up In Blue guitar (my 1969 Martin D-28) lives on in the archives of the Bob Dylan Center in Tulsa, well worth a visit for fans of all generations. www.bobdylancenter.com

ko 4/22/2024